Despite its reputation as one the top public middle and high schools in the country, Albuquerque’s Cottonwood Classical Preparatory School has struggled since its 2008 opening to find a physical home to match its stellar academic record.

Over its 14 years, the public charter school has opened in a too-small space, expanded into a split campus, moved to a new, bigger but still inadequate space, and, most recently, begun expanding that space.

Every phase of its physical growth has proved time-consuming, expensive, and potentially distracting from Cottonwood Classical’s academic mission. When a current expansion project is completed early next year, the school will take a pause on what has seemed like perpetual expansion and construction.

But even more will be needed eventually, said John Binnert, Cottonwood Classical’s executive director. That’s why he expresses great enthusiasm over a new law passed unanimously this year by the New Mexico state legislature that will make the financing of charter school facilities simpler, more straightforward, and, thanks to a new state low-interest revolving loan fund, more affordable.

“I’m excited and very appreciative of the legislators who have sponsored and carried and supported the bill,” Binnert said in a recent interview. “You want your own state to be proud and have confidence in and be supportive of good schools. It’s not that our state government didn’t want to do that. But this was important to really show charters in their state that they are supported.”

House Bill 43 includes several provisions that should provide immediate help to at least some of the state’s 98 charter schools. The new facilities law the bill creates will:

- Create a $10 million Charter School Facility Revolving Fund. The fund won’t be used for construction but will be available for schools currently in lease purchase agreements to use for refinancing. Only charter schools that are established and have been renewed at least once are eligible to tap the fund.

- Ensure that available public land and facilities not used by school districts will be offered to charter schools.

- Standardize what is currently a $700 per student lease assistance payment for charter schools. The amount of lease assistance charters currently receive is unpredictable because it is allocated based on the square footage of instructional space in schools, as measured by the Public School Capital Outlay Council.

- Help charter schools get onto school district bond funding elections and distributions.

State Rep. Joy Garratt, a Bernalillo Democrat and the bill’s cosponsor, said established, high-quality charter schools deserve support. “If a charter school has proven itself it really deserves to have proper facilities,” Garratt said. “It was an equity and fairness issue that made me want to support this.”

Garratt said the bill’s accountability provisions are an important part of the package. To be eligible for the loan fund, a charter has to have gone through a renewal process at least once, and to have undergone two successful audits.

“It shows that this is a school that’s on track for success academically, financially, and administratively,” Garratt said. “I felt that a school that has gone through that process deserves greater assistance in either paying off their facilities, paying off the lease, or constructing a new facility.”

Charters struggle with facility costs, logistics

Cottonwood Classical provides a clear example of why this legislation has been sorely needed. The school originally opened in a small building behind the Unser Racing Museum that IndyCar racing legend Al Unser and his wife Susan made available to the new school.

“The school would not have been able to open if they had not stepped in,” Binnert said. “And it shouldn’t take that. If you have an approved charter, there should be another way in with facilities.” The new law’s mandate that unused school district land and buildings be offered to charter schools could be a big help in this regard.

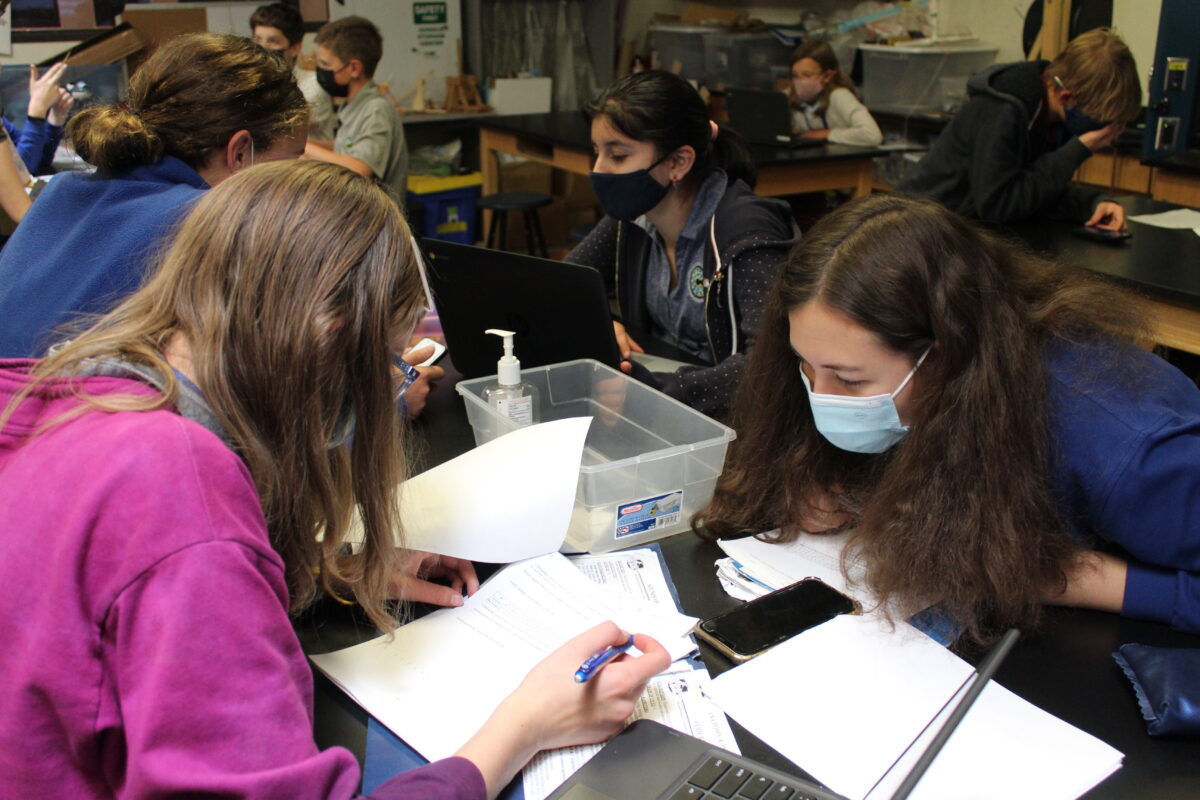

Cottonwood Classical, which offers the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, was an instant hit. Enrollment grew from 121 students to 372 in its first three years. It has carried a lengthy waiting list ever since, even as it has continued to increase the size of its student body.

It wasn’t long before Cottonwood Classical outgrew its space, and had to rent a second building down the street from the museum. It was close enough for students to walk between the two buildings, but it was not an ideal setup. And it was expensive to lease two separate buildings.

In 2012, a nonprofit Cottonwood Classical Foundation formed to help with fundraising, and located a potential new facility: a 47,000-square-foot building on a six-acre lot in the Journal Center business park. The foundation helped secure the facility through the issuance of bonds, a long, laborious process. The school relocated to that facility in 2013.

“And within two years, we had outgrown it,” Binnert said. The school, bursting at the seams with almost 750 students, purchased some additional land a couple of years ago, creating a 10-acre campus. During the pandemic, to help maintain social distancing, portable classrooms were installed on the undeveloped portion of the land. But that was only a temporary fix.

Cottonwood Classical developed a plan to build a 24,000-square-foot addition onto its existing building, which would increase student capacity to 960. Again though, it was a laborious, expensive process, requiring the services of “a brokerage in Chicago, a bank in Denver, and a public finance authority in Wisconsin,” Binnert said. The addition will allow the school to add a full gym, a cafeteria, and a library, as well as classroom space.

It has taken a tremendous amount of effort from many people, Binnert said: “All of this requires a group of volunteers, doing all of this work. And paying for attorneys to get a broker who then shops the school project around for someone who feels that investing in a school is worth it.”

Even after all of that work concluded successfully, the school needs to raise an additional $1.3 million through a capital campaign to fully fund the expansion.

From Binnert’s perspective, a couple of components of the new law will help other schools avoid some of the logistical headaches Cottonwood Classical and other New Mexico charter schools have faced with facilities over the years.

First, changing the lease assistance program from being based on an arcane square footage calculation to a straightforward $700 per pupil will inject some certainty into budgeting. “Having lease assistance tied to enrollment, like every other funding source we have, is huge, because it makes that funding stream more predictable.”

Because Binnert knows this latest expansion project won’t be the school’s last, future access to the revolving loan fund will be even more helpful down the road. Even before that, refinancing some debt through the fund would be helpful, he said.

Having such a fund available “just makes all the sense in the world, especially when you have established charter schools that have proven that they have a successful model,” Binnert said.

Bipartisanship was key to passage

Bill cosponsor State Rep, Cathrynn Brown, a Carlsbad Republican, said she supported the legislation because she helped launch the Jefferson Montessori Academy Public Charter School in Carlsbad 20 years ago, and remembers well the challenges posed by securing a facility.

“Having to use operating funds to pay for a facility is a distinct disadvantage, especially to a school just getting started,” she said.

Brown said she was “delighted” that the effort to get the bill passed was bipartisan. In the past, she said, some legislators who opposed charter schools grudgingly said “OK, we will let you have life, but we will not help you pay for a facility,” she said. Over the years, though, charter schools have proven themselves to be a valuable addition to the public education landscape.

“Some of the legislators who were so opposed are still serving. They became supporters because they’ve had a chance to meet constituents who have children in charter schools,” Brown said. “And some of those early charter school students have become adults and they have helped make the case for treating charters better than in the past.”

State Rep. Garratt, the other cosponsor, and a recently retired 28-year veteran teacher, said a lot of credit for the bill’s passage should go to charter advocates like Matt Pahl of the Public Charter Schools of New Mexico organization. The bill was amended several times in a collaborative effort with advocates to ensure its passage, Garratt said.

“Their openness to really solving the problem made a huge difference,” Garratt said. “Sometimes we come to educational issues with passionate differences on our educational philosophies. But when people really work together, you can solve problems. This bill is evidence of what true collaboration can produce.”

The time was right in 2022 to