Albuquerque Collegiate Charter School Sets Example for Extended Learning Time

Jade Rivera, founder and executive director of Albuquerque Collegiate Charter School, doesn’t hesitate for even a beat when asked how New Mexico’s Extended Learning Time Program has benefited her school.

With the majority of Albuquerque Collegiate students entering school already lagging in basic academic skills, every hour and every day of school is precious, Rivera said. The state’s Extended Learning Time Program funds an additional 10 days of school per year for all students. That can make a big difference.

Still, according to a report from the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, 43 of the state’s 89 school districts “elected not to participate in any sort of extended school year” during the 2021-22 academic year.

That’s puzzling to leaders like Rivera. “More time means more learning for scholars,” Rivera said recently. “We want that learning to be really impactful and targeted to their individual needs.”

The school, now in its fourth year, currently serves 160 kindergarten through fourth-graders. It will expand to fifth grade next year.

Despite the learning challenges the Covid-19 pandemic brought to schools across the country, Albuquerque Collegiate is seeing signs that its extended day is paying dividends. Although comprehensive data is hard to come by since the state paused its standardized testing in 2020 and 2021, local information through the Istation formative assessments the school administered last fall show that Albuquerque Collegiate students are making solid gains.

“We are seeing significant rates of reading proficiency at least two times that of the local district and state that we attribute certainly to the overall academic program, but also to this extra time for learning which we see as core to our overall academic program,” Rivera said.

Statewide, mid-year Istation data for K-4 in the 2021-22 school year showed that just a quarter of students tested were reading proficiently. At Albuquerque Collegiate, 55 percent of students were proficient. That doesn’t satisfy Rivera, but it tells her the school is recovering more effectively from the pandemic than are many other schools.

“It (55 percent) is definitely not where we want it to be. Our goal is to get closer to the 80 percent range for our scholars by end of year,” she said. “But we also recognize the really deep impacts of learning loss over the last two years for students.”

Albuquerque Collegiate’s academic day is significantly longer than a regular elementary school in Albuquerque Public Schools, running from 7:30 a.m. to 3:15 p.m. – just under eight hours, compared to six hours per day for most APS elementary schools.

The $80,000 in ELTP funds the school received this year also allows Albuquerque Collegiate to offer a free after school care program to all of its students, free of charge. This is a tremendous boon to working-class parents, who often lack the work-hour flexibility to pick their children up from school in the middle of the afternoon, when most public elementary schools dismiss.

Between the ELTP and the after-school program, Albuquerque Collegiate students can be in school from 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., five days per week.

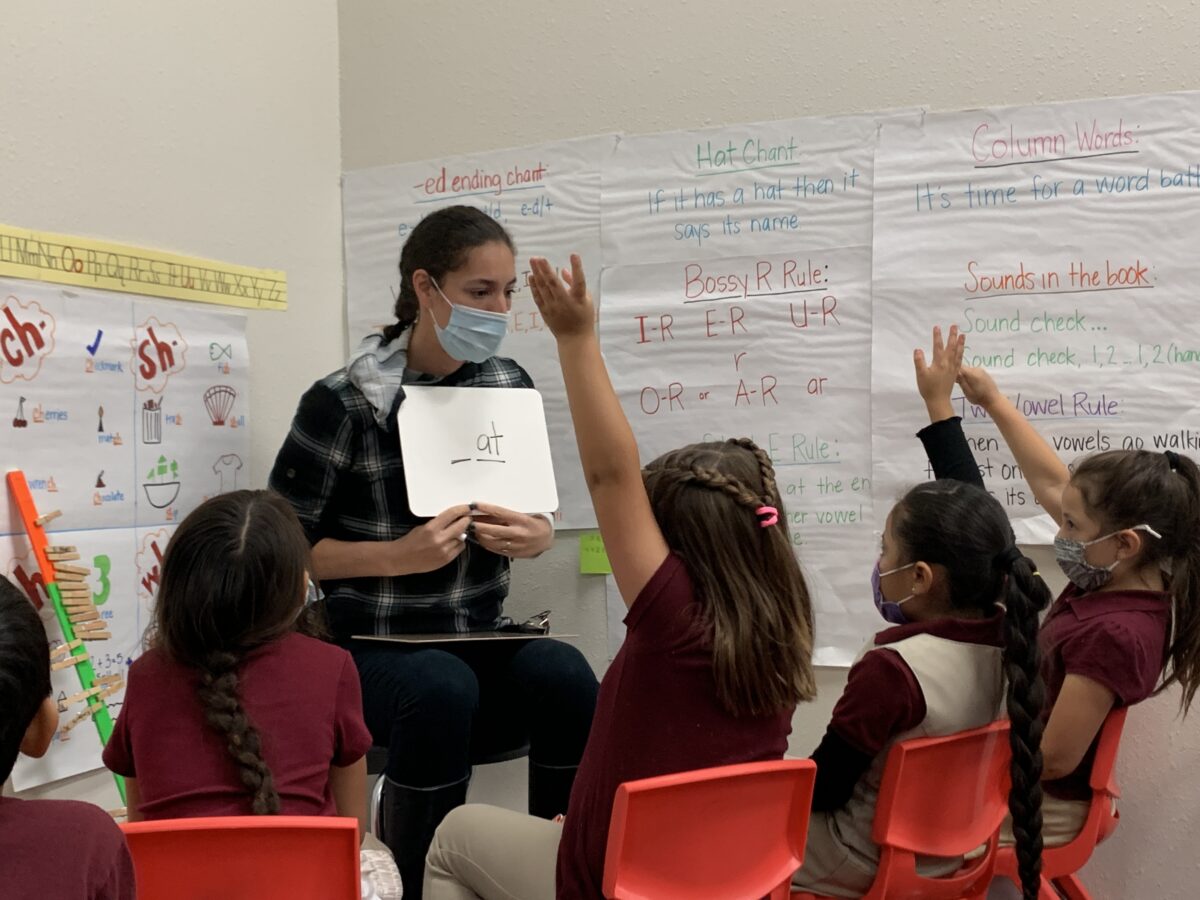

While those after-school hours are vitally important to parents, it’s the extra academic time that has made a difference for students. In grades K-2, Rivera said, about 40 percent of school days are spent on “foundational literacy instruction.” Making sure students can read on grade level by the end of third grade sets them up for success in later grades, when they will be “reading to learn” instead of learning to read, she said.

“You can’t pick up a science book and gather content if you don’t have foundational literacy skills in place, Rivera said. “It’s really important to us that we have those solid foundational literacy skills in K-2, so that our students in third through fifth grade are able to dive more deeply and more meaningfully into their other content areas.”

If the state didn’t offer the ELTP, Rivera said, “we would still run our same calendar – it’s that important.” But this would require sacrifices elsewhere in the school’s budget. “We’re able to keep more dollars in our classrooms, and provide the supports that our teachers and scholars need to be successful. Having this additional time is critical to that success.”

Younger students, whose early primary years have been hit hard by the pandemic, are especially in need of the extra time, Rivera said. This year’s second-graders experienced multiple disruptions to their first-grade year. So Albuquerque Collegiate is using its extra hours and days to backfill first grade standards while simultaneously working to keep those second-graders doing their grade-level work.

Rivera, an Albuqueruqe native, founded Albuquerque Collegiate after serving as a Teach for America Corps Member. She returned to New Mexico to work in the Public Education Department during the administration of Gov. Susana Martinez. She then completed a rigorous Building Excellent Schools fellowship. That program prepares young educators to open high-performing charter schools.

Despite the learning challenges the Covid-19 pandemic

Finke:

Finke: