Editor’s note: Crystal Tapia-Romero was elected last November to the Albuquerque Public Schools Board of Education. She is a lifelong area resident and a graduate of APS’s West Mesa High School, located in the district she now represents. Romero-Tapia is Executive Director of the New Mexico Early Learning Academy, as well as a prominent advocate for early child education on the state and national level. She also has three children who are in or who have been through APS.

New Mexico Education recently spoke with Tapia-Romero about her background, her views on public education, and her goals and ambitions for APS. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

New Mexico Education: Please tell us a bit about your background and how you became involved in early childhood education.

Crystal Tapia-Romero: My mom used to be a kindergarten teacher and then chose to expand into opening early child care programs in her home, and then through our church, and then went independently on her own. It was my mom’s blazing the trail before me that exposed me to early childhood education.

But honestly, I had no desire to get into education back almost 25 years ago. I went in strictly to help my mom. I had come from the retail side of things and with my sales experience I knew I could add some insight helping get new families enrolled. My dad passed away and I stayed to help my family. I remember telling my mom like I’m not here to stay, I’m just here to help out. And I never left.

NME: What happened that caused you to stay?

Tapia-Romero: I just fell in love with the profession. Children are so much fun to be around and to this day, my favorite job I have ever been in was being a pre-K teacher for a year. And over the years I’ve been able to expand my knowledge and experience base and take it into advocacy.

I realized there were a lot of people in Santa Fe and on the federal level who were making decisions for our business, our organization, our classrooms, but who had never set foot in a classroom. And I was like, oh gosh, this does not make sense. So little by little I started getting more involved, going up to Santa Fe, talking with some of our legislators, introducing them to what it is we do, inviting them to visit our location, to see first-hand what our teachers are doing.

NME: What made you decide to run for school board?

Tapia-Romero: I had actually thought about this for years, even before COVID. Once I got involved in advocacy work, I enjoyed being able to make positive changes on behalf of our industry. I remember talking to my mom several years ago and saying, “What if I run for school board?” State representative or senator didn’t interest me, because kids are my passion.

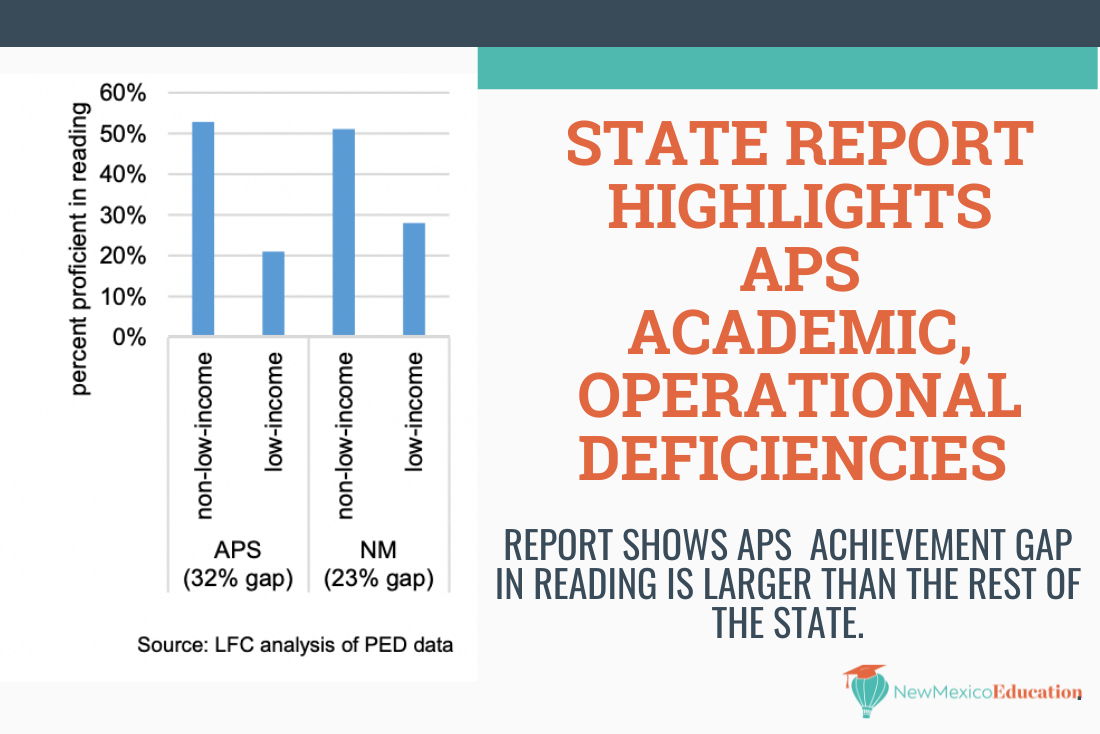

And having my own kids in the public school system, I always thought there was something we could do better. I’m one of those individuals who believes, and I know it sounds so clichéd, but if you’re going to talk about a problem, you need to be part of the solution. People always talk about how bad APS is or how New Mexico ranks so low in education, how we’re at the bottom. But no one wants to come with the approach of being solutions-oriented.

Once COVID hit I couldn’t just sit back and pretend that it was okay. It was literally right before our eyes. We were seeing our own child’s education decline. At that time our daughter was a senior, 18 years old, taking online classes. She would be in her room with a blanket over her head, camera off, and completely disengaged. My husband and I were saying to each other, ‘this isn’t working.’

At the same time, I would sit online and watch school board meetings. And I’d be thinking, oh my gosh, they’re just going round and round. I felt like they weren’t being productive. They weren’t making choices that were best for my students. I was looking at all of them and thinking, goodness, I don’t think any of them have a child in the public school system. I didn’t feel that the choices they were making were affecting them directly.

I sat down with my husband one day when he came home from work and I said I want to run for school board, but I can only do it if you’re in it with me l00%. I knew the commitment it would take to run for this office. And he didn’t hesitate one bit in supporting me and said you got this. Let’s do it.

NME: Now that you’ve been on the board for a few months, what do you see as the biggest challenges facing the district?

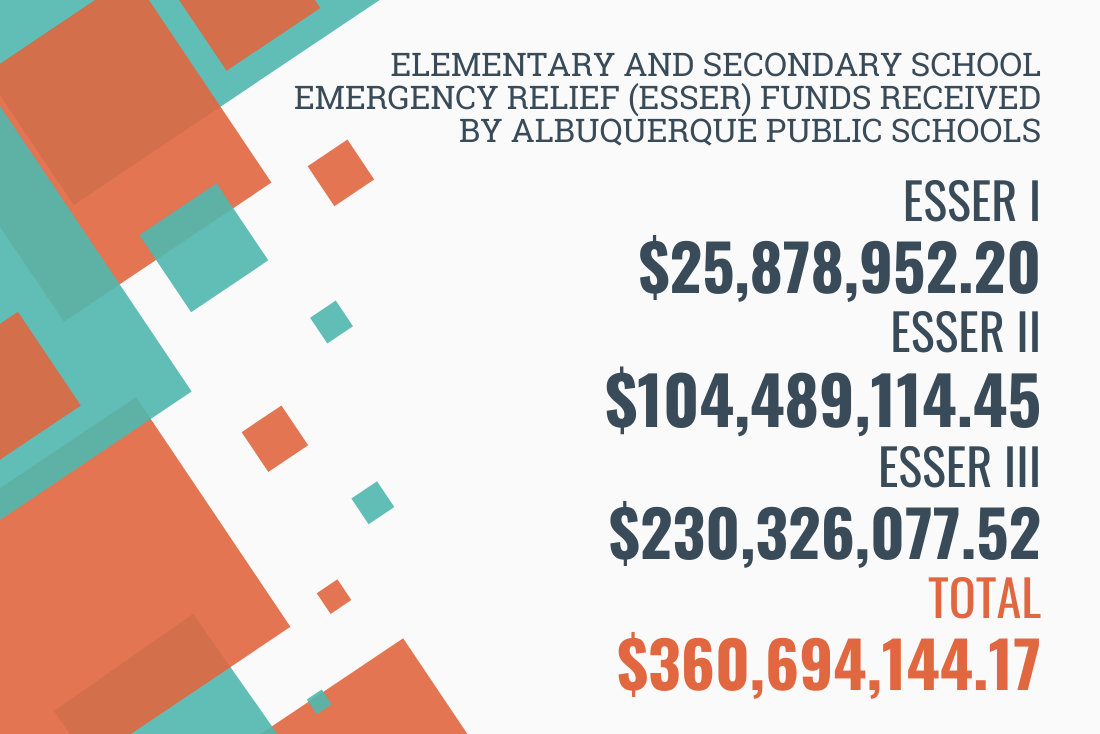

Tapia-Romero: One of the biggest eye-openers since being on the board has been in relation to the budget, and being privy to a ton of information that I didn’t have access to before. I used to look at this massive budget and think, ‘it’s a spending problem, not a money problem.’ Now I realize it is a whole lot more complicated than that.

Yes, there are some things that we need to buckle down on and make sure we don’t have loose spending. But when our budget is tied to our enrollment, and we have a mass exodus of students leaving our district, we’re having to make some significant adjustments.

Recently, our legislators and the governor signed off on giving our teachers a significant raise, which in my opinion, was long overdue. However, the amount of money that was budgeted for APS for these raises still left us with a $5 million deficit. It wasn’t enough. So where does that money come from?

I am still trying to understand how quickly we can make better use of our money. How can we make good use of the federal dollars versus state dollars, and understanding that certain money could only be spent in a certain places. It’s not just moving it from one category to the next. It’s not that easy.

NME: Other than the budget, what other challenges are you seeing?

Tapia-Romero: Enrollment is a huge challenge and ties back to the budget. Another is renewing trust in the district. I want us to be accountable, to maintain open communications at all times. That sounds great, but I want to make sure it is more than empty words, that we really put this into play. That part has been challenging, because there’s so many times the media doesn’t accurately represent what we’re doing.

NME: Can you say a bit more about that?

Tapia-Romero: The most recent thing we dealt with was the Extended Learning Time. [Editor’s note: A split APS board recently voted down a mandatory 10-day extension of the school year and a longer school day, allowing schools instead to opt into the fully funded program if they so choose].

The media was reporting that the district was going to have our students in school starting as early as July after ending in June, so they would only have a few weeks off for summer break. That was a complete lie. I don’t know how else to say it. It was a straight-up lie.

And what happens is when the media gets to everybody before we’re able to actually get the whole story out, then everyone has already drawn their own conclusions. So then we get all these parents telling us ‘our students need a break, you’re taking their summer away, we won’t have time for vacation,’ or ‘our kids need to work during the summer.’ But that wasn’t what we were doing, by any means.

If someone really looked at the calendar that we were proposing, it was going to add a couple of days before the traditional school year started and a couple of days after. The majority of other days were going to be absorbed in the middle of the school year. I wish that we would have been able to get ahead of what the media was reporting, to really give an accurate picture of one of the ideas we had to pull APS out from the bottom. Was this going to be an ultimate solution to our education crisis? No. But it was a step in the right direction, and a big missed opportunity.

NME: Do you believe this opportunity is now lost permanently?

Tapia-Romero: We were able to pass a vote that would allow each individual school to choose to have Extended Learning Time. So it’s not completely dead. Some schools and districts will take advantage of it. I know my district desperately needs it.

NME: What gives you hope for the future of APS?

Tapia-Romero: Our district is completely overloaded with the amount of work that needs to be done and the outcomes that they’re trying to produce. Ultimately, they were just kind of just running by the seat of their pants and whatever happened happened and no one was really intentional about the goals of the district. This new board decided on developing a whole new strategic plan for the board and district. Something that’s really going to make us all accountable, and be relevant to where the district is today. Some of us came together and said, we can’t keep operating like this. We need to learn from other districts that are doing well, that come from similar demographics and challenges. I feel like we’re on the right path to do that.

We need to bring in some outside people who can really help streamline this and make us pull our head out of the weeds. I believe the people who can come up with new ideas and visions aren’t the people within the district. They have enough on their plate right now. And there’s no way we can ask them to do more. It’s really hard to be innovative when you’re the person who’s been stuck in it day in and day out.

NME: Can you talk about the significance of the recent election and the change in the board’s composition?

Tapia-Romero: What is different about the three of us, Courtney (Jackson), Danielle (Gonzales) and myself is that we’re moms who have children within the district. We’re also graduates of our own districts: we went to school in the districts we represent. So this is very personal to us.

Speaking for myself, and I think it’s true of the other two ladies as well, we’re going to shoot you straight. We’re not here for all this fluff and fancy filler words. We are going to ask the hard questions, and we’re ready to work. And obviously we’re not there for the glory, because you don’t get paid to serve on these boards.

We’re determined to make changes and to make sure we’re doing what’s best for our kids. That’s why we’re here.

"Enrollment is a huge challenge and ties