New Mexico ranks dead last nationally on NAEP test results

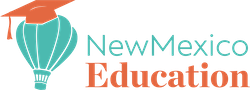

New Mexico’s fourth- and eighth-grade students took a big step backwards in math and reading during the Covid-19 pandemic, newly released data from gold-standard national tests shows.

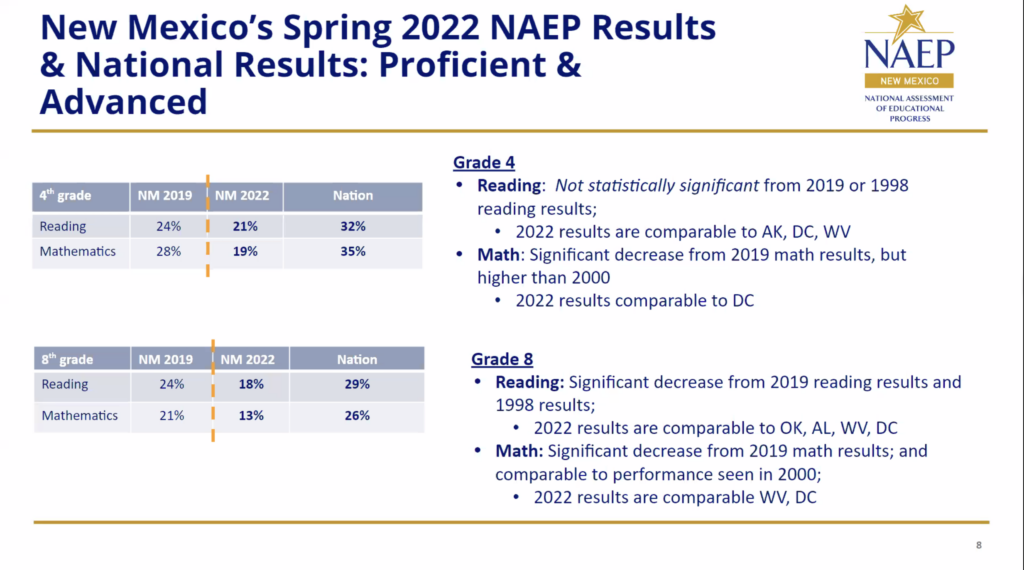

According to results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), commonly known as the Nation’s Report Card, New Mexico students, like their peers across the country, had lower proficiency rates on NAEP tests in 2022 than any time in recent memory. The scores were the lowest in a range from 13 to 30 years, depending on the grade and subject.

While the national news was grim, it’s even worse for New Mexico, which ranks dead last among the 50 states and Washington D.C. on all four tests – fourth and eighth grade reading and math, according to charts compiled by the New York Times.

In a meeting with district and charter school leaders Monday morning, New Mexico Education Secretary Kurt Steinhaus acknowledged the challenges but tried to rally the troops with a pep talk.

“I would say from the chair I sit in this doesn’t knock us off our game,” Steinhaus said. “One of the phrases that echoes in my head is we can do better and we will do better. In fact, I think New Mexico is already doing better in mathematics and reading and it’s because of the hard work you all are doing there in New Mexico in trying to to move that needle.”

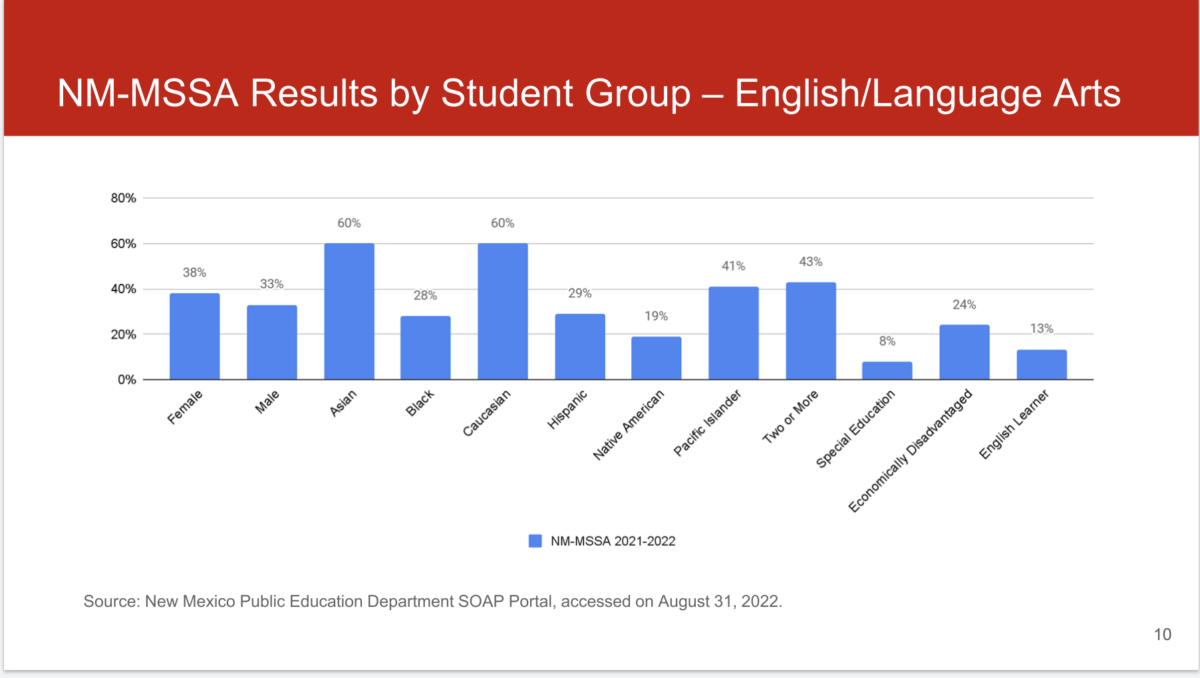

It’s hard to draw optimism from the NAEP numbers, however:

- 4th grade reading proficiency: 21%

- 4th grade mathematics proficiency: 19%

- 8th grade reading proficiency: 18%

- 8th grade mathematics proficiency: 13%

These results put New Mexico’s 4th grade math proficiency at its lowest point in 17 years (since 2005), and its 4th grade reading proficiency at its lowest point in 13 years (2009). Results for 8th grade follow similar trends with math proficiency hitting its lowest point in 30 years (since 1992) and reading at a 15 year low (2007).

Amanda Aragon, executive director of NewMexicoKidsCAN, a nonprofit that advocates for community-informed, student-centered and research-backed education policies, said the NAEP results leave no room for complacency.

“Many New Mexicans have become far too comfortable with a bottom of the list ranking for education in our beautiful state. Today’s results sound an urgent call to action,” Aragon said. “To create the change our system needs, every one of us should ask ourselves what we can do to ensure our students receive the education they deserve. We must come together and demand urgent action.”

Steinhaus said in his travels across the state this school year, he has seen encouraging signs that learning will accelerate. “My advice to you at your school district or your charter school is to stay on your path. Keep moving forward. Let’s give our teachers and our hard working staff out there a little pep talk. Let them know good work they’re doing day in and day out is appreciated and recognized and that’s what it’s all about.”

The National Assessment Governing Board also released results Monday of the Trial Urban District Assessment (TUDA). Albuquerque Public Schools is among 27 districts that participate in that program.

NAEP-TUDA results showed that in APS:

- 4th grade reading proficiency was at 25% — the lowest since 2017.

- 4th grade mathematics proficiency was at: 24% — the lowest since TUDA was first administered in 2011.

- 8th grade reading proficiency was at 21% — the lowest since 2017.

- 8th grade mathematics proficiency was at 17% — the lowest since TUDA was first administered in 2011.

New Mexico’s fourth- and eighth-grade students took