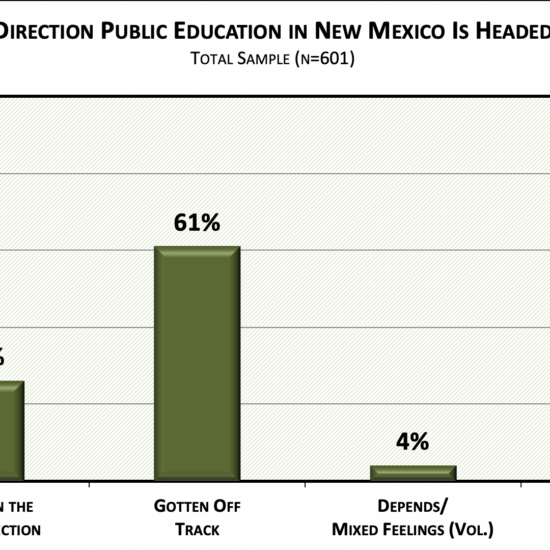

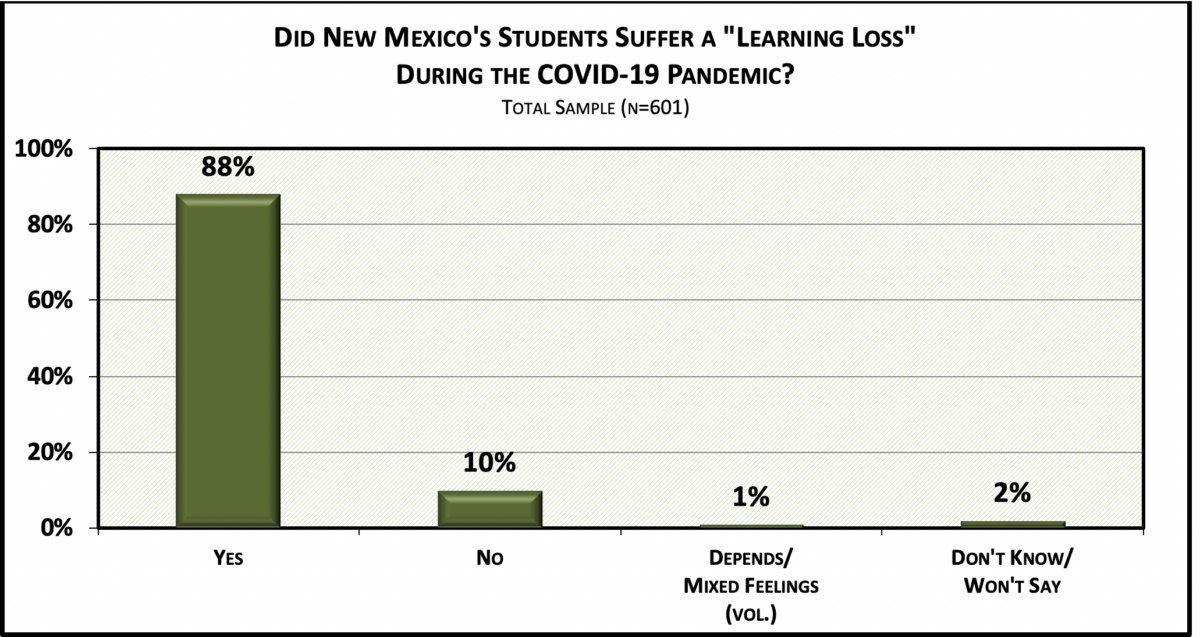

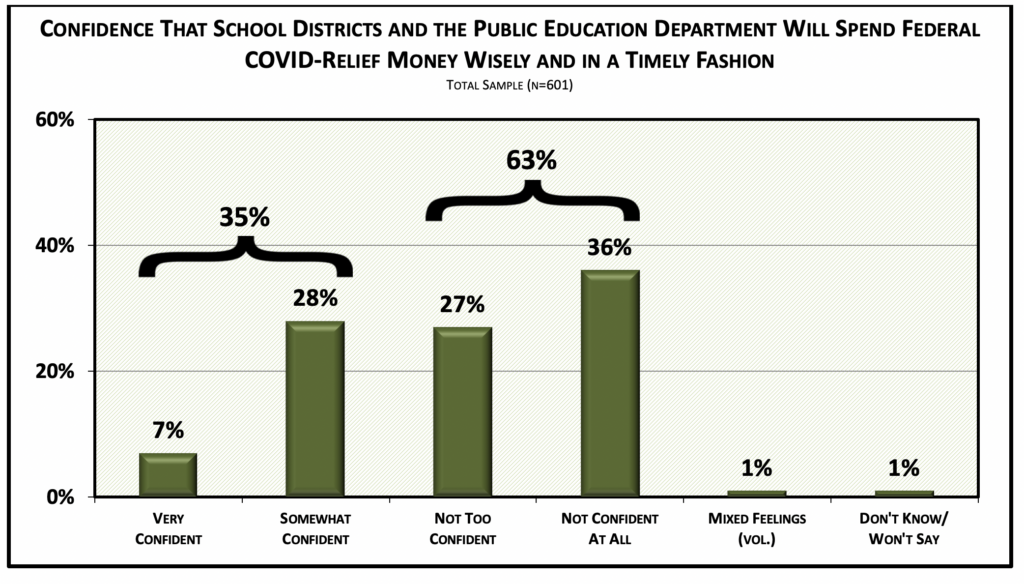

An overwhelming percentage of New Mexicans believe students suffered learning loss during the Covid-19 pandemic, and two-thirds lack confidence that the state or school districts are doing enough to make up that lost ground.

Those are among the findings from a new poll commissioned by a consortium of education advocacy groups and conducted by Research & Polling Inc., an Albuquerque-based polling firm.

Asked whether they felt students suffered learning loss during the pandemic, 88 percent of respondents answered yes. And 63 percent responded that they aren’t confident that the Public Education Department and school districts “have a plan to get students back on track.”

And only 19 percent of respondents gave state education officials high marks for their handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, while half said the state has done a poor job.

On the questions of pandemic learning loss and state and district plans for overcoming it, there were minor variations in responses based on gender, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and geographic location.

Slightly fewer women (85 percent) than men (90 percent) felt that learning loss occurred, and fewer Hispanics (84 percent) than whites (93 percent) said students lost ground. Some 82 percent of the lowest income households surveyed – those earning under $20,000 per year– believed learning loss occurred, while 91 percent of people in households with incomes of $100,000 cited learning loss as significant.

Geographically, respondents in northwest New Mexico were most likely (91 percent) to identify learning loss as real, while those in the north-central region were least likely (83 percent).

Opinions about education officials’ handling of pandemic recovery broke down along similar lines.

Those numbers seem about right to Tennise Lucas, a New Mexico educator for more than 25 years who is currently the college and career director at Mission Achievement and Success (MAS) charter school in Albuquerque.

From her perspective, Lucas said, the pandemic took a huge toll on kids both academically and emotionally, and recovery will take a concerted and deliberate effort that few schools and districts seem willing or able to undertake.

“Nobody expected (the pandemic) and so unfortunately, when it happened, everyone was scrambling for technology, for internet service, for a lot of things,” Lucas said. “And high risk populations suffered most because they just don’t have the resources in their homes.” This was especially true in tribal areas, she said, that often lack reliable internet access that’s a necessary precondition for remote learning.

Learning loss was also especially acute for students who aren’t safe at home, because being trapped in an unsafe environment makes learning impossible, Lucas said. “They could have been at home with their abuser or they could have been at home with somebody who didn’t like them. They were babysitting their siblings. You have such a wide range of things that you have to look at. A lot of times people don’t realize how social-emotional wellbeing and academics go together.”

At MAS, Lucas said, leadership and staff have made a concerted effort ameliorate the impacts of Covid-19 learning loss. There are coaches at every grade level, people who check on every absent student every day (attendance has been a big problem everywhere post-covid), and a series of social-emotional supports.

But Lucas expressed dismay at what she has seen and heard about what other schools and districts are doing – or not doing – to surmount these challenges. “Some districts and systems just aren’t spending their (Covid relief) money like they should, in attendance coaches, social workers, places where people can have an actual impact.

“Maybe don’t give superintendents big raises when their districts aren’t performing.”

Ashley Carpenter, the mother of four school-age children who attend both district and charter schools in Albuquerque and Santa Fe, said the pandemic had a devastating impact on her children’s education and emotional wellbeing. In some cases, she said, schools are doing a good job trying to patch things up. But in others, school efforts leave much to be desired.

Her two older boys, now 11 and 14, were hit especially hard by having their in-person learning disrupted, Carpenter said. “They didn’t have that kind of connection and that instruction that they needed,” she said. “They are both very extroverted so they need that contact. Even if they got one-on-one time with a teacher, it was a struggle to get them to grasp the concepts they needed to get and would have gotten if they had been able to work in person.”

Her oldest son, now a freshman at an Albuquerque high school, struggles to interact with peers now that school is back in person, even though that was never an issue for him prior to the pandemic, Carpenter said. But she credited the school with having supports in place to support struggling students.

“They are doing a good job trying to get kids reintegrated,” she said.

Her two youngest children, who attend the Albuquerque Sign Language Academy charter school, are doing well, thanks, she said, to the “amazing” supports the school has in place. “They have a lot of therapists and other experts on board to help with the social emotional aspect,” she said.

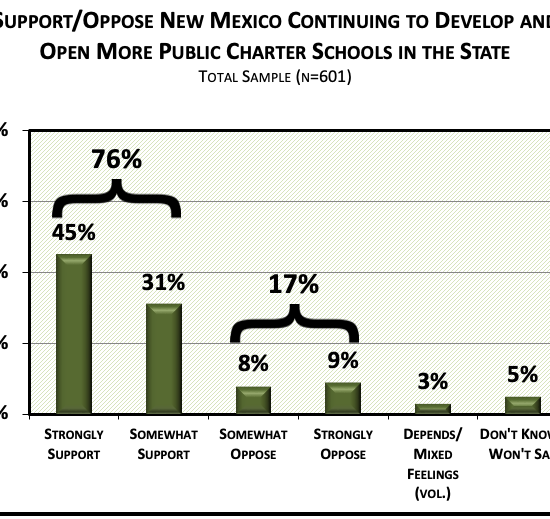

Pollsters conducted interviews of 601 New Mexicans in August, and the poll has a margin of error of 4 percent. It was commissioned by NewMexicoKidsCAN, Public Charter Schools of New Mexico, Excellent Schools New Mexico, the Greater Albuquerque Chamber of Commerce, and Teach Plus New Mexico. It touched on a range of issues, including perceptions of the quality of education in New Mexico and perceptions of and support for charter schools.

New Mexico Education will be reporting on other poll findings in the coming days and weeks.