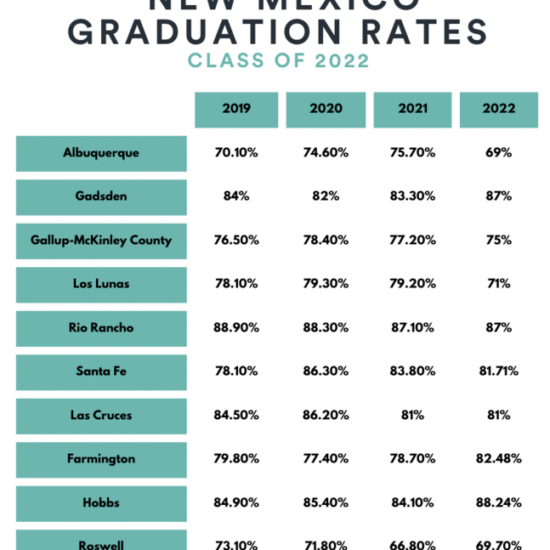

Two of New Mexico’s 10 largest public school districts – Albuquerque and Santa Fe – have reported significant increases in graduation rates since the Covid-19 pandemic began two years ago.

Given the pervasive evidence about learning loss and the devastating impact on students of the social isolation the pandemic caused, these numbers raise more questions than they answer.

According to data compiled by New Mexico Education, Santa Fe schools saw a 7 percent increase in graduation rates between 2019 – the last pre-Covid year – and 2021. In 2019, the SFPS graduation rate was 78.1 percent, and in 2021 it was 83.8 percent.

Albuquerque Public Schools’ graduation rate increased by 8 percent from 2019 and 2021. In 2019, the APS graduation rate was 74.1 percent, and in 2021 it was 75.7 percent.

Six of the other eight largest districts saw moderate dips in graduation rates post-Covid. The two exceptions were Roswell, which reported a larger 9 percent drop, and Los Lunas, which reported a 1 percent increase.

Under federal regulations, the on-time “adjusted cohort graduation rate” is calculated by dividing the number of students graduating by the number entering ninth grade four years earlier. New Mexico is unusual among states in that it uses a “shared accountability” model. This means, according to the PED, that any high school a student attends is assigned a portion of that student’s ‘outcome,’ whether that is graduation in four or more years, or dropping out before graduation.

The Brookings Institution, a centrist think-tank, in writing about national increases in graduation rates even before the pandemic, said such claims should be viewed with some skepticism.

“Social scientists know that when it comes to numbers and accountability, Campbell’s Law needs to be kept in mind: “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor,”” Brookings wrote in a 2018 report.

“Campbell’s Law is cited regularly in discussions of achievement-test scores, but high schools are accountable for their on-time graduation rate, so the law would apply to it,” the report continues.

Still, districts and the state’s Public Education Department were quick to trumpet the figures as good news coming out of the pandemic. “It’s reassuring that even amid the pandemic’s second year, New Mexico’s overall graduation rate held steady, with many groups seeing improvement,” Public Education Secretary Kurt Steinhaus said in a press release. “We’re grateful to students, families and educators for the hard work it took to achieve that.”

Albuquerque Public Schools released a video earlier this month highlighting its graduation rate successes featuring interviews with Superintendent Scott Elder and several high school principals. In the video, Elder attributed improved rates to “efforts of the people at the schools.”

“…families are buying in and they’re saying, “No, I want my kid to graduate.” They recognize that it makes a difference in their future life and it’s just so important. I’m really pleased to get here and I hope we continue to improve,” Elder said.

Del Norte High School Principal Ed Bortot said his school has created a personalized, caring culture. “It’s about creating positive relationships and knowing that you’re not just a number on this campus,” Bortot said in the video. “We know you. We know who you are when we bring you in. We care about you. It’s about a belief system. It’s about telling our kids, number one, “We believe in you. We know you can do this.”

Remediation rates are not mentioned in the four-plus-minute video.

New Mexico makes it difficult to put graduation rates in perspective, because the state does a poor job of collecting and reporting data on how many high school graduates enter college in need of remedial classes because they aren’t prepared for the rigors of college-level work.

The New Mexico Higher Education Department’s website provides a remediation percentage for each year’s graduating class. But the website has not been updated since 2020, and provides just a one-sentence explanation and no underlying data, making any meaningful analysis impossible.

The most recent remediation rate listed on the site, from the fall of 2000 was 25.33 percent.

Graduation rates decoupled from remediation rates provide an incomplete picture. Theoretically, a school district could decide in the wake of the pandemic to graduate most students, regardless of their grades, because learning was severely disrupted and students shouldn’t be punished for circumstances beyond their control. That would show up as a higher graduation rate.

This kind of manipulation would be captured, at least for students entering community colleges or four-year colleges, by a corresponding rise in remediation rates – the percentage of students required to take non-credit bearing classes to get them to the academic level of an incoming freshman. But the state’s remediation rate information is both out-of-date and woefully lacking in detail.

In some states, students must pay for remedial classes but get no college credit for them. This can be discouraging, especially for low-income students for whom the unanticipated expense is especially burdensome.

In New Mexico, however, most remedial classes are credit-bearing, according to the Higher Education Department, and are covered by the state’s Opportunity and Lottery Scholarships, which provide full college tuition funding to many of the state’s college students.