A new law that substantially increases the pay of individuals who specialize in teaching Native American public school students their tribal and pueblo languages and dialects does a great deal more than just give big raises.

The new law, House Bill 60, helps ensure that these languages, many of which are passed down orally and have no written form, do not die out.

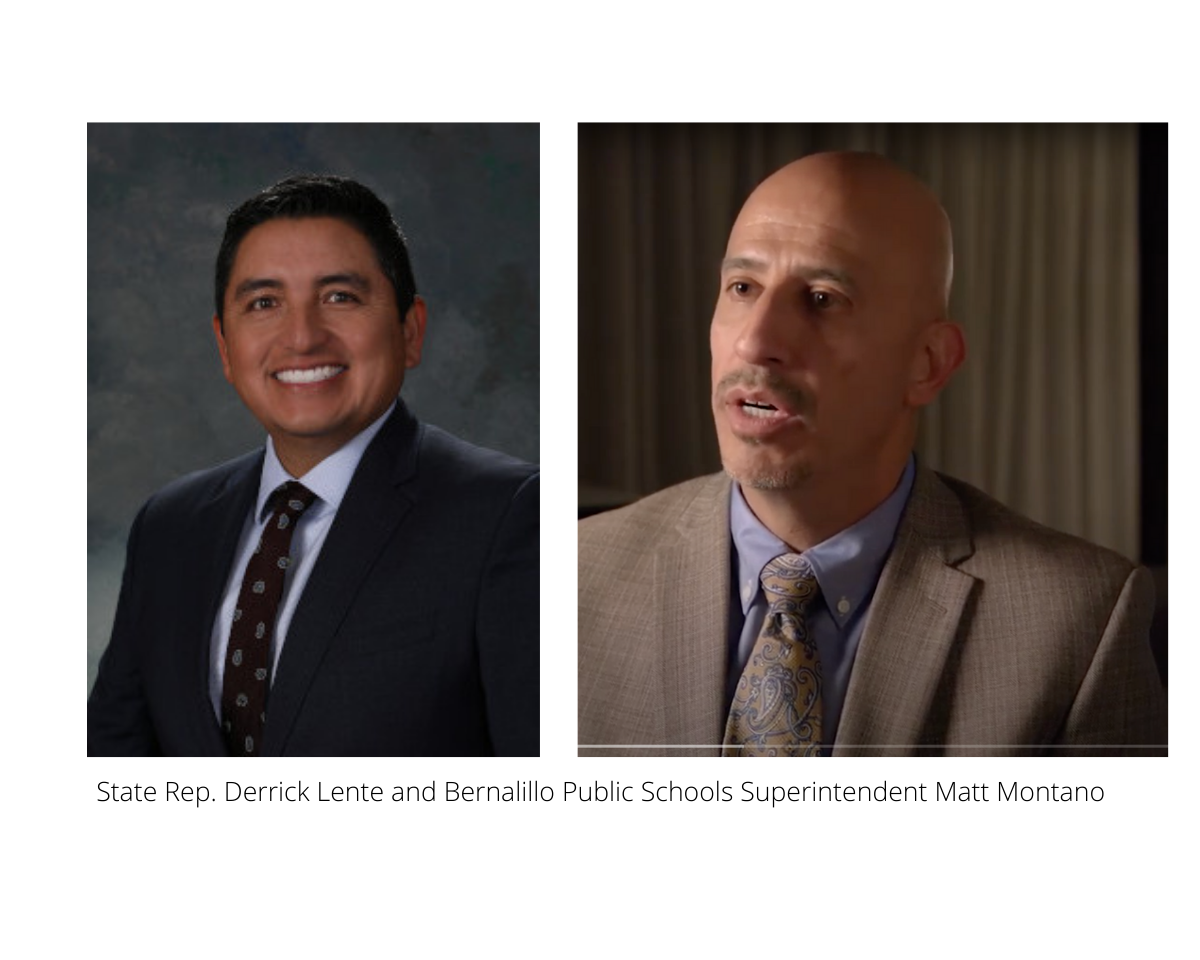

State Rep. Derrick J. Lente, the Sandia Pueblo Democrat who sponsored House Bill 60, said while in some cases these languages are taught at home, reinforcing them in school helps keep them alive, and that is important to the culture overall.

“Language, as Native Americans, is at the core of our culture,” Lente said. “It’s that mother tongue that our forefathers and our ancestors gifted us with, and that’s what will ensure survival as Native Americans. To have this now validated as an essential part of the public school framework, with our native tongue teachers being compensated as fairly as any other second language teacher, is a huge step towards educational equity.”

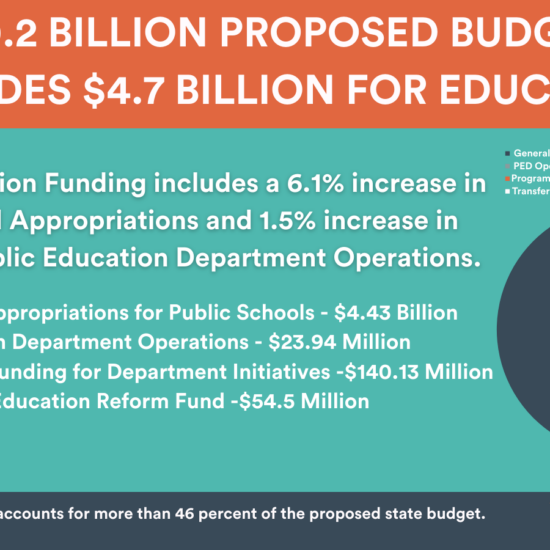

Until HB 60 passed and was signed into law, people who held Native American Language and Culture Certificates were paid as instructional aides, most of them earning between $12,000 and $15,000 per year for full-time work. Now, they will be paid as Level 1 teachers, which, under another bill passed this year, means at least $50,000 per year.

Lente credits Bernalillo Public Schools Superintendent Matt Montano with pioneering the equitable pay for Native American language teachers, as well as advocating effectively for the bill.

Montano, who became superintendent last August, moved immediately to hike the pay of those instructors to Level 1, which at the time was $43,000. Almost half of the district’s 3,100 students are indigenous.

“When I came back as the superintendent, I made this a priority of mine,” Montano said. “We promote these programs from an equity lens, but we weren’t actually effectively supporting the teachers the same way that we were promoting the program.”

Montano, a former principal in the district, occupied a senior position in the Public Education Department during the administration of Gov. Susana Martinez. From both perspectives, he saw a need for the state and school districts to pay more than lip service to honoring native cultures.

“It’s a values statement,” he said. “We’re saying that we value your language, but we’re not actually valuing your language because part of the equity lens comes in your budget. And so I think that was a huge statement for us to reinforce with tangible action.”

Lente, who has served in the state House of Representatives since 2017, said he has been working on educational equity issues for New Mexico Native Americans since the Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico federal court case was decided in 2018. That ruling mandated sufficient funding to ensure an equitable education for all of the state’s public education students.

“That ruling presented perfect timing and a perfect place where I was at in the legislature to begin to push educational equity bills,” he said.

Lente said he and other education advocates held convenings of the Apache and Navajo nations as well as the state’s pueblos to begin discussing the most effective strategies for promoting true educational equity in the state. What resulted was the Tribal Remedy Framework, endorsed by the 23 pueblos, nations and tribes indigenous to New Mexico.

One logical and important piece of the framework was making Native American language instruction for Native American students a permanent and stable fixture of public education in the state.

HB 60 will also help increase the number of Native American language teachers, Lente said. Many of the current and prospective teachers are tribal elders, he said. “No college or university teaches these oral languages and so these elders are in their own rights doctors of our indigenous tongue.”

To become a teacher of Native American languages, an individual must be verified by a tribe, nation, or pueblo as what Lente termed “linguistically blessed” and able to impart that knowledge to young students.

“Let’s say Joe is a janitor at Bernalillo High School, and he is also a tribal elder who knows his native tongue,” Lente said. “There are a number of great supportive organizations that can help Joe to develop curriculum and skills to be an effective classroom teacher.”

Montano said he is encouraged that Native American high school students in particular have shown eagerness to learn their languages, and the high school programs are growing. He said when he returned to the district after more than a decade away, he noticed a palpable sense of energy and pride in the native language classrooms.

“What I’m finding is this sense of belonging that maybe hasn’t been there before,” Montano said. He said the higher salaries have helped promote “a bigger sense of belonging for the professional teachers in the classroom, and that transfers onto students. Students take pride in knowing their language and being able to exhibit it in a place other than their pueblo.”