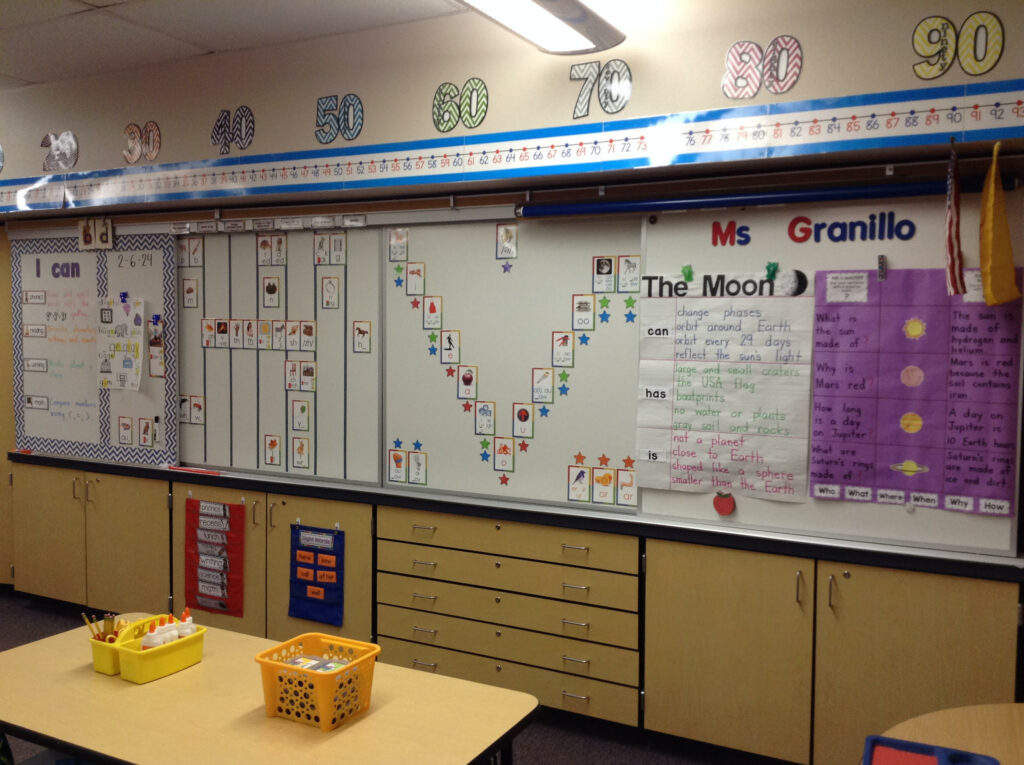

The following Op-Ed was written by Chelsea Granillo, a first-grade teacher at Vista Grande Elementary School in Rio Rancho Public Schools. She is a National Board Certified Teacher in language arts and a 2023-2024 Teach Plus New Mexico Alumni Policy Fellow.

Every day, as a first-grade teacher, I change the trajectory of my students’ lives through one simple act: Teaching them how to read.

As a student teacher, I was fortunate to have been trained by a gifted kindergarten teacher as my mentor. She taught me impactful literacy strategies, such as guiding children to generate word lists based on spelling patterns and building up their phonemic awareness skills to help them blend sounds together when reading simple words. Now, it is my turn to set my students up for success, as I welcome 24 tiny children into my classroom every day so I can teach them how to read.

These strategies, which I use in my classroom every day, are now especially timely. Three years ago, New Mexico launched a statewide structured literacy initiative to help students become proficient readers by focusing our teaching on the five important components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Based on a law passed in 2019, all first grade students must be screened for dyslexia within the first 40 days of the school year so kids who need help receive it immediately. Most elementary teachers, like me, are also enrolled in ongoing professional learning called LETRS, which helps bridge reading research to actual literacy instruction in the classroom.

While this legislation is a good start and research shows it takes years to see a significant increase in reading scores, we must do more. On the 2023 NM-MSSA assessment, just 38 percent of students were deemed proficient in language arts, up four percent from the previous year. Here are three solutions our state should consider:

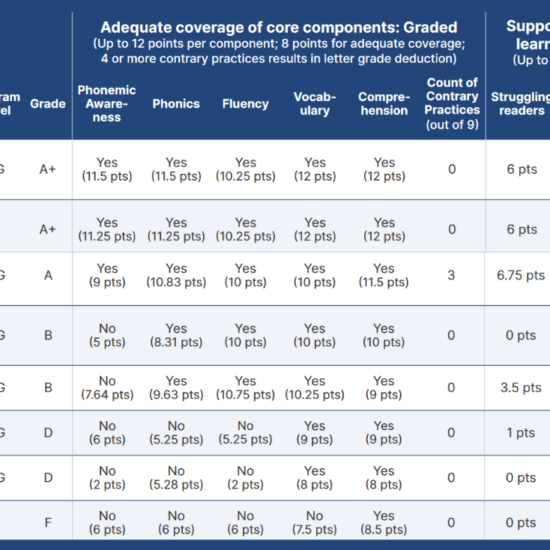

Ensure structured literacy is part of all state teacher preparation programs. According to the National Council on Teacher Quality’s review of how teacher preparation programs are covering the core components of structured literacy, the University of New Mexico, New Mexico’s largest university, received a ‘D’ grade for its undergraduate teacher program and an ‘F’ grade for its graduate teacher program. Embedding the LETRS professional development course into teacher preparation programs would prepare future elementary educators by giving them the tools they need to teach early literacy skills before they step into a classroom, such as developing children’s oral language and linking sounds to letters. If I had received LETRS training during my college career, I would have learned how to adequately plan language arts lessons that balance word recognition and language comprehension, instead of depending on my mentor teacher to teach me the building blocks of reading as a student teacher.

Require every school to adopt a high-quality structured literacy curriculum. Two years ago, I served as a member of my school district’s instructional materials adoption committee. We approached adopting a new curriculum thoughtfully by determining local priorities, using rubrics to evaluate program components, and listening to presentations made by each publisher. I encourage other districts to form teacher-led adoption committees and to choose from the state’s comprehensive list of structured literacy curriculums that have been reviewed by local educators. It is alarming to me, as an educator, that the state does not require local education agencies to adopt a curriculum from this list. This means that school districts could still choose curricula that teach children how to read through instructional practices that are contrary to research, such as guessing at words based on the picture a child sees. Requiring all schools to choose instructional materials from this list would provide students equitable access to materials based on the most recent reading research.

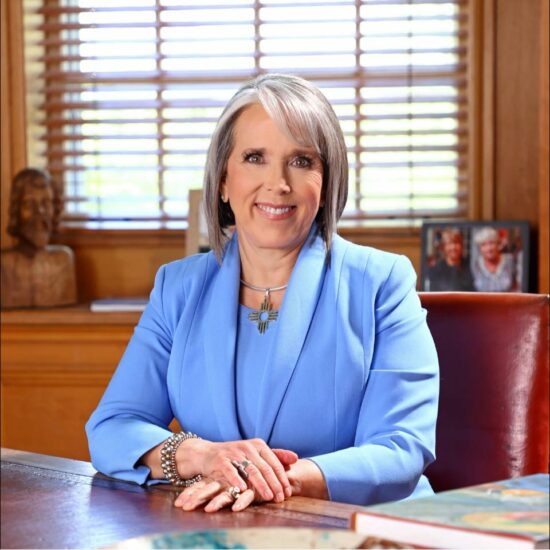

Hire a structured literacy coach at every school. In my school district, every elementary school has its own instructional coach to support teachers by modeling effective instructional practices in early literacy and guiding grade levels in forming data-driven intervention groups during data studies. In her recent State of the State address, Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham asked the legislature for $30 million to fund this initiative, particularly for the lowest-performing schools, which would help provide support for students who are not reading on grade level. The legislature should allocate these funds.

My mentor teacher shaped me into the reading teacher that I am today because of the hundreds of hours I spent observing her lay a foundation in literacy for her students. I teach language arts every day with a strong sense of urgency because reading is a survival skill. I urge our lawmakers and state officials to mirror my sense of urgency when making decisions about how to improve outcomes in reading. Our children’s future success and economic prosperity depends on their ability to read.