Editor’s note: Mission Achievement and Success Charter School (MAS) opened in Albuquerque in 2012, led by founder JoAnn Mitchell. She had been authorized to open a school serving students in grades 6-12. But after just a couple of years, Mitchell concluded that the school needed to start working with students from their earliest years of schooling, to keep them from falling behind.

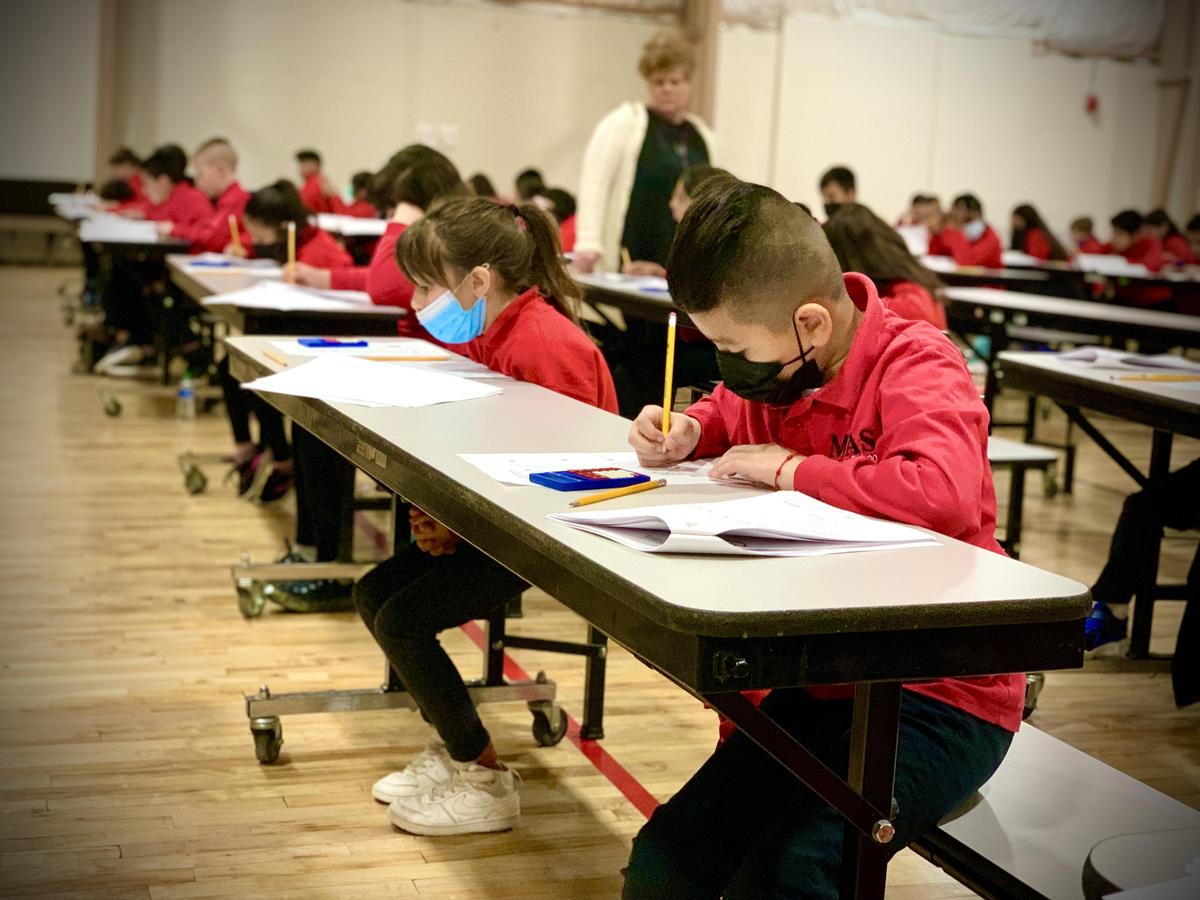

Today MAS serves more than 2,000 students in grades PreK-12, and has a lengthy waiting list. MAS stands out for having all of its students graduate high school, with 100 percent being admitted to college or the military. Its literacy and math achievement rates are far higher than Albuquerque Public Schools, the state of New Mexico as a whole, and even the suburban Rio Rancho school district.

Mitchell’s own compelling story, and how she built MAS into the highly successful school it is today is the subject of the interview below. It has been edited for length and clarity.

New Mexico Education: Having a 100 percent graduation rate is almost unheard of, especially for a school that works with a student population facing multiple barriers.

JoAnn Mitchell: I always feel I need to throw in a disclaimer. If you look at the Public Education Department website, it shows us with a 90-something percent graduation rate. That’s because in New Mexico, we operate on a shared accountability model. That means any student who ever attended MAS counts for or against your graduation rate. So if a student came here for one semester as a freshman and then transferred and later dropped out, that student is counted against our graduation rate.

But any kid who’s come here and stayed, regardless of when they came, we have gotten them to graduate. We’re obsessive about stalking kids down. We’ll drive to their house to get them to school. We’ll go to any means possible to make sure kids are successful. And when kids do leave here (transfer to another school), we try hard to keep track of them. You can’t track every kid but we try really hard to have good conversations with families about where they are going. About 50 percent of them end up not graduating (from high school).

NME: Tell us a little about your background and how you ended up opening a charter school focused on low-income students in New Mexico.

JoAnn Mitchell

Mitchell: Until the last five to seven years I never used to share my personal story, because some of it is painful. But over time I have learned how impactful it is for people to hear it.

My parents were teen parents, high school dropouts in Upstate New York. We grew up in poverty. I mean, we were very, very poor, rural poor. It was an abusive household. I was surrounded by domestic violence and abuse. I grew up in extensive fear of my dad. It was a very dysfunctional environment. It was by the grace of God that I got where I was, and broke the cycle of poverty in my family.

I was able to attend my Catholic church’s school, and that gave me a strong academic foundation. But a lot of my academic success was based on a complete fear of my father. I developed into a perfectionist. I remember coming home over the winter break in third grade crying because I had a test coming up in January, and I had that much anxiety about whether or not I would pass the test and what would happen to me if I didn’t.

It’s not like I was exceptionally smart. I worked my ass off. That’s really what it was. So I tell people that it’s kind of dysfunctional, how I achieved in school, it was fear. It was complete fear. But it changed the trajectory of my life.

That same fear propelled me to excelling on the New York Regents Exams, and that gave me the opportunity to go to college. Sometimes people ask me “who was your champion? Who was that person in your life who really believed in you?” I don’t want anybody to feel sorry for me, but I didn’t have that person. Nobody in my school was like, “Oh my God, you and you’re so smart. You have so much promise.” I never heard that from a counselor or a teacher, anybody. Me leaving and going to college was literally to get out of the dysfunction.

NME: Coming from the background you just described, what was the transition to college like for you?

Mitchell: I went to Elmira College in Upstate New York. I didn’t even know the difference between a private college and a state university, but that’s where I ended up. And it was total impostor syndrome at first. All these kids driving Mercedes and new jeeps, and I didn’t even have a bicycle. I had no idea what I was doing. I wanted to be an elementary education major but I ended up registering for a lot of the wrong classes. I didn’t struggle so much academically but I really struggled with the culture of college. I didn’t know how to navigate the systems. So much of the way I have structured MAS is based on my first-hand experiences.

NME: What was your path after college?

Mitchell: I got married and my now ex-husband was a professional minor league hockey player, so we moved around a lot. I got hired into Title I (high-poverty) schools wherever we went, because there were always job openings. We lived in Florida, Georgia, New Mexico, and then back to New York. I worked in some of the poorest, most rundown schools you can imagine, especially in Columbus, Georgia.

I got fascinated with why some kids were steered into special education when I didn’t see much of a difference between them and kids who weren’t in special ed classes. It opened my eyes to the inequities around education. A lot of times special ed can be a sentence for a kid. I became fascinated by this and so I got my Master’s in school psychology.

In New Mexico I got a job as principal of the school inside the Youth Diagnostic Development Center (the juvenile detention center in Albuquerque). I loved the job. I loved working with the kids, who had just had so much trauma in their lives and made bad decisions.

I found a sweet spot for kids who have been underserved. So I worked there for a couple years, ended up getting divorced, moved to New York, and worked in a charter school in Harlem.

That was my first experience in a charter school. It allowed me the opportunity to understand what a charter was and recognize that there might be a better way to do things. That’s what inspired the idea to open a charter. I felt that autonomy allows you to do some things that are unique.

NME: How did you end up back in New Mexico?

Mitchell: I’ve lived and worked in several places across the country, and I learned that despite different ethnicities, kids and their needs and challenges just weren’t that different from place to place. But in New Mexico I found that the educational challenges were pretty profound. I felt like if there was ever a state that had a need for high quality education, it was New Mexico. So it was a very intentional decision to come back here. I also felt that this was a great place to live.

I was working on the charter application and flying back and forth from New York. That was 2010, 2011. I came here without a job and got a job while I was waiting to get the charter approved. So it was really a leap of faith, a complete leap of faith to try to make this happen.

And here we are. Fast forward 10 years later, we celebrated our 10th year anniversary this year.

NME: How did you decide on the educational approach and philosophy that drives MAS?

Mitchell: Moving around as I did with my ex-husband and his hockey career, I was exposed to a lot of different schools and models. In Columbus Georgia I experienced working in a school with really dire poverty and a student population that was almost all Black. In New Mexico I learned a lot about working with second-language learners. In New York I got to visit some phenomenal charter schools.

So the philosophy of MAS was a hybrid of a lot of different experiences and a lot of my own reading and my love of learning about what I saw work in various places. And my own experience of having grown up in situations similar to a lot of students I’ve worked with just gives me a different lens on things than a lot of other educators have.

All the parents I’ve worked with over the years love their kids, just as my parents loved me. Sometimes that doesn’t show up in ways that we would consider socially appropriate. So I felt strongly that we needed a school that involved parents. We needed a school that pushed kids to be able to access college, regardless of where they began academically. We needed a school that provided full inclusion for kids who were identified as having special needs.

And above all, we needed a school that changed belief systems. You have to change beliefs and mindsets. That’s not pushing my values on kids. It’s changing that limited mindset, that I’m not capable, that I’m not smart, that I’m not good at school, that certain people are meant for college and it’s not for me.

A lot of times with our families it’s not that they’re not pushing their kids because they want to hold their kids back. They just don’t know what that other side of the world looks like.

It’s all about opening doors of opportunity. That involves three things. It’s academic, it’s the culture of college, and then deep, deep changes and shifts around mindset, really helping with those resiliency skills, really helping with the self advocacy, really helping with the problem solving, the perseverance, the grit.

Those things are values that if somebody doesn’t teach you, I don’t know how you develop them over the course of life unless you stumble upon them. I was lucky enough to have that happen to me, but why leave it to chance?